The golden age of design in American parks was, ironically, the Depression.

The Civilian Conservation Corps, a new federal relief program meant to put America back to work, sent 3 million displaced laborers out across the continent to restore and enhance the nation’s public lands. Some were craftsmen, recent immigrants who brought Old World skills and perspectives to the task.

Among the greatest beneficiaries: national parks, where the CCC built countless lodges, cabins, shelters, bridges, stone gateways and walls, dams, sheds, trailhead markers – proud, iconic structures, still admired and enjoyed by visitors today.

Bainbridge Island has a new park feature inspired and informed by the CCC era: a rock-and-timber bench shelter at Pritchard Park. Nestled into the bluff overlooking the mouth of Eagle Harbor and west toward the Seattle skyline – its view, eagle-eye straight to the Space Needle – the rustic shelter is crafted from local materials and wholly at one with its Northwest setting.

“We hadn’t built a structure like this, basically a small bench-shelter combination,” said David Harry, park services superintendent for Bainbridge Metro Parks and the shelter’s co-designer. “We’ve got benches all over the place with no roof over them. We’ve got shelters much larger than this, but with picnic tables inside. It’s a new concept for us, but in the 1930s, these structures were built all over the U.S.”

The memorial shelter was privately funded by the Parsons family, in honor of their daughter Carrie and other families who have prematurely lost their children. The family thanked the Park District staff including Dan Hamlin, David Harry, “and the wonderful park services department crew for their help in the design and construction of this beautiful structure.

“It is our hope that this will be a place of rest and comfort for the Bainbridge community in the future.”

The gift was made through the Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation. Said Mary Meier, executive director: “It’s an extraordinary shelter, honoring the donors’ wishes and crediting the skills of the Park District team. We’re proud to have played a part by channeling this gift for the community to treasure and enjoy.”

INFORMED BY A CLASSIC ERA

“In any area in which the preservation of the beauty of Nature is a primary purpose, every proposed modification of the natural landscape, whether it be by construction of a road or erection of a shelter, deserves to be most thoughtfully considered. A basic objective of those who are entrusted with development of such areas for the human uses for which they are established is, it seems to me, to hold these modifications to a minimum and so to design them that, besides being attractive to look upon, they appear to belong to and be a part of their settings.”

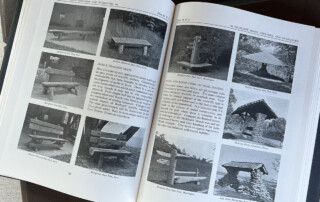

So wrote Arno B. Cammerer, then National Park Service director, in his foreword to the 1938 edition of “Park and Recreation Structures” by architect Albert H. Good. A lavishly illustrated, 3-volume survey of CCC-era park design and construction, Good’s tome would become a bible in the field.

Vintage editions are rare and even reprints fetch a fair sum; David Harry keeps a copy on his desk. Challenged to design a shelter that would soar above standard “park-itecture,” Harry turned to the Good book.

He knew the vernacular of the period well, having supervised restoration and construction at historic Crater Lake National Park in the 1990s. While there, he learned from one of the park’s original stone masons, who came from Italy in the 1920s, plied his craft at Crater Lake through the CCC years, and still lived in the area.

“He showed us the innuendos in a stone wall that you don’t know until you build one,” Harry said, “placement of rock, how to break up joints and add interest with the stones selectively placed.”

Designed by Harry and Doug Slingerland, the Park District’s creative manager, the Pritchard Park shelter melds forms and concepts from several illustrated plates in Good’s survey. Per Good, indigenous materials would be key for harmony with the landscape.

The shelter is buttressed by two tapered columns of regionally sourced rock, each stone thoughtfully, if back-achingly, hefted into place by the construction team and mortared secure. (A refinement from the earlier age of construction: the stones are fashioned around concrete-and-steel-reinforced columns, anchored in turn to a concrete slab.) Three cedar trusses, milled from nuisance trees harvested at Hidden Cove Park, span the seating area. The shelter is crowned by a pitched, cedar shake roof.

Handcrafted wooden benches are contoured into the columns at each end. The area between the benches is open, so someone visiting in a wheelchair will have the very best seat.

Interestingly, the work uncovered evidence of Pritchard Park’s past as the community of Creosote. Dozens of row houses, stores and other structures once lined the hillside, a whole company town built above and around a sprawling plant that turned out treated pilings for most of the last century.

Site work uncovered the concrete steps and footings from the Creosote mill town. Archival photos show a building on the site, although its purpose is lost to history.

Other, natural vestiges remain, atypical pine and apple trees that may have been planted by Creosote residents. The Parks & Trails Foundation-supported Student Conservation Corps worked the area over the summer, and ecological restoration is ongoing.

Find the shelter at the east end of Pritchard Park, just up the bluff trail from the lower parking area, or down the trail from Rockaway Beach Road. It’s also visible from the ferry, which glides below the shelter in striking relief.

“It’ll become pretty iconic to the park and to the island itself,” Harry said. “I’d like to build more of these, but you have to be very careful about where you put them. You don’t want too many, and you want them in the right places. Very special, very select places.”