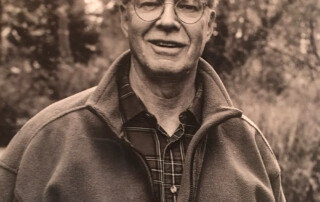

He was a product of suburban Long Island, N.Y., who found deep connection with the environment as a Northwest rower and mountaineer. An engineer for a defense contractor, who organized anti-nuke meetings during his lunch hour. A patient, owlish presence at public meetings for decades, who was never shy about keeping the City’s feet to the fire on environmental regulation.

When the Charles Schmid Waterfront Trail is formally dedicated on July 7, you could make a good case that it’s as much for Schmid’s years as the avatar of environmentalism islandwide as for his work on the trail itself.

“I think just seeing the natural beauty, the spectacular mountains around here, was a big philosophical influence on his caring for the planet,” says his daughter, Jenny Schmid. “He was so passionate about mountain climbing, and he approached that the same way he approached the Waterfront Trail – slow and steady wins the race.”

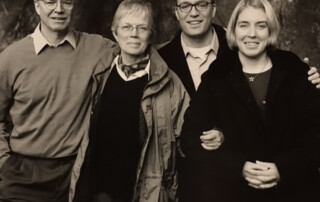

Charles Schmid brought his family to Bainbridge Island in 1970 – wife Linda, and young children Andrew and Jenny. It was a quieter island then, maybe 7,000 people. Local government was confined to Winslow, with the rest of the island under the county thumb in distant Port Orchard. The Schmids’ Manitou Park Boulevard neighborhood was still known to the post office as “Rural Route 7.”

But the idyll of a still-bucolic island masked growing environmental problems.

Today’s Vincent Road recycling station was still the town dump, an open pit dug in the 1940s that had quietly been collecting hazardous waste. At Bill Point, the Wyckoff creosote plant turned out telephone poles and treated pilings by the thousands, all the while polluting the harbor and beach with toxic goop.

If he wasn’t an activist when he arrived, Charles Schmid soon became one. He and Linda were autodidacts, sponging up the literature of the nascent ecology movement and applying it at home on everything from conservation to recycling.

“They were way ahead of their time,” son Andrew Schmid says. “Environmentalism (in the 1970s) was more of a theory or a concept, or a political thing. Dad looked at it as a utilitarian thing, something to be fixed.

“He mostly looked at it from a rational standpoint, that you don’t just throw away a bunch of things that don’t need to be thrown away.”

GRASSROOTS ENVIRONMENTALISM

Island activism in the 1970s was grassroots in the truest sense. Islanders criss-crossed back roads to meet in kitchens and living rooms, sharing information and concerns.

The Schmids helped found the Association of Bainbridge Communities in 1978, an umbrella organization for preservationists in Murden Cove, South Bainbridge, Bucklin Hill and other neighborhoods. Their clarion was the ironically titled “Scotch Broom,” a quarterly journal that brought environmental news, commentary and even poetry to island mailboxes.

Charles Schmid became an early advocate for growth management, worked on the (unsuccessful) 1979 Washington bottle bill, helped start local recycling before it was offered commercially, and championed Home Rule, the movement for all-island government and local land-use control.

He commuted to Seattle for the better part of 25 years, working for a defense contractor that his friends chided as “the bomb factory,” but still organized nuclear awareness meetings and attended peace events.

“I don’t know that any of the other engineers were super-psyched about talking about the Cold War and nuclear arms development,” Jenny Schmid says. “But he had a strong idea about what was the right thing to do.”

While many island activists railed for better ferry service to the island, commuter Schmid stuck to environmental causes. Year by year, newsletter by newsletter, meeting by meeting, the tide turned for the environment.

The Wyckoff plant was shut down in 1987, declared a federal Superfund site and cleaned up to create today’s Pritchard Park. The Vincent Road dump was dug up in 1992-93, decades worth of garbage and sludge hauled away, and a modern recycling and transfer facility built.

ABC and the Scotch Broom were labors of love for a close-knit group of islanders. To keep them going (and sometimes defray legal costs), Schmid and friends held an annual bicycle raffle at the Grand Old Fourth, one more chance to fly the environmental flag.

“He loved people, and he loved that Fourth of July booth,” Jenny says. “He loved talking to people, whether they agreed with him or disagreed with him. He just loved talking with people about the issues he cared about.”

Home Rule succeeded in 1991, bringing land use control back to Bainbridge Island in time for islanders to fend off a 1,200-home planned community – with a store, restaurant and private ferry terminal – at Blakely Harbor. From that victory, Blakely Harbor Park was created.

Janet Knox, a friend and colleague in environmental circles for many years, says Schmid was driven by a strong “sense of place” and belief in a shared, islandwide identity that the new City of Bainbridge Island validated.

“We are all one island,” Knox says, “and that’s something that Charles really, really believed.”

Said Frank Stowell, another longtime colleague: “I was really impressed his thoughtfulness, how smart he was, how good he was at organizing people. ABC was full of a lot interesting, disparate personalities, and Charles was the steady hand that guided it all through. I’ve always thought of Charles and Linda as (part of) the ‘Rodgers and Hammerstein’ of Bainbridge environmentalism.”

Schmid became president of the Acoustical Society of America, allowing him to work from Winslow and spend his lunch hours rowing quiet Eagle Harbor. He became a tireless advocate for a waterfront trail, and public access to the shoreline and waters that he enjoyed so much.

There were losses (bureaucracy doomed a footbridge to lower Madison Avenue) and wins (developers stepped up to build the overwater walk from Pegasus to the Pub). When he wasn’t advocating at City Hall, Schmid planted trailside trees in Waterfront Park and kept them watered from buckets he toted around in a wagon.

“Even his family didn’t know what he was up to, but he treated those little trees like they were his kids,” Andrew says. “He realized that just having a trail wasn’t all you needed, it had to look nice and you needed trees there. A lot of those trees are probably still there.”

The Bainbridge Island City Council formally designated the Charles Schmid Waterfront Trail in 2022. Mary Meier, Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation executive director, said the honor was well earned.

“We owe so much to those who helped preserve and protect the community we enjoy today, and Charles Schmid is certainly high on that list,” Meier says. “It couldn’t be more fitting to honor Charles for his advocacy for trails and shorelines as a resource we can all share and enjoy.”

Schmid was honored with the prestigious 2020 Washington Governor’s Volunteer Service Award for Environmentalism. Slowed by health and mobility issues in his final years, he still walked the Waterfront Trail with the aid of a walker until shortly before his passing, in April 2022, at age 81.

A bench at Waypoint Woods now honors Charles and Linda Schmid, who survives him. Jenny believes the Charles Schmid Waterfront Trail designation honors them both, even though there’s only one name on the sign.

“They did all this together, and she really influenced the way he thought,” she said. “As a couple they really talked through the issues, and shared this passion for the environment.”

CHARLES SCHMID WATERFRONT TRAIL DEDICATION – Celebrate the dedication of the Charles Schmid Waterfront Trail at 11 a.m. Friday, July 7, at Shannon Drive in Waterfront Park. New interpretive and wayfinding signage will be unveiled, and a new printing of the Charles Schmid Waterfront Trail map. The event is co-hosted by the City of Bainbridge Island and the Bainbridge Island Parks & Trails Foundation.